Reflection Eater

Lucy Zhang

Mom used to hit my forehead with the bamboo chopsticks if I stared in front of the mirror too long. She’d catch me poking at a mole next to my eye, scratching dry skin from my nose, baring my teeth to reveal the pink of my gums and the receded parts exposing my bone. “The longer you stare into the mirror, the more it has a chance to learn your habits, behaviors, facial expressions until eventually, once it’s ready, it will emerge from the glass and take your place,” Mom warned. “The guardians sent by Huang Di can’t patrol the gates between worlds forever.” But what terrified me more than getting replaced by some lurking entity in the mirror was Mom not recognizing the real me. I was convinced nothing could mimic the way I packed my lunch and hid my Tupperware container in the back of the fridge so Dad wouldn’t accidentally take my portion, the way I hung red silk threaded knots on all of the unused hooks and hangers because I liked seeing my handicraft on display, the way I slept on the corner of my pillow so there’d be enough room for the cash fairy to slip money under my pillow if I scored 100% on the Chengyu quizzes. I never earned full scores, always forgetting definitions or accidentally smudging the ink on my arm so I couldn’t make out my cheat notes.

After Dad leaves Mom, she spends less time watching me and more time to herself in the study, emerging only to refill her mug of tea or cook another kettle of water. She asks me to bring her a bowl of rice and a soy sauce marinated egg for lunch and eats in front of her computer, sticky fingers moving back and forth between bowl and keyboard. This leaves me free to stare into the body-length mirror resting in the master bedroom closet, positioned on a slant against the wall, sweeping over me from feet to neck like I’m a tower-long beanstalk. In front of the glass, I try on thigh highs and qipaos and silk Wensli scarves, paint eyeshadow and glitter over my eyelids, let my hair out of its ponytail and release the tension on my scalp.

On Mom’s birthday for which I’ve prepared a popup card, the result of one blunted Exacto knife and a stack of ruined cardstock, it pulls me into the glass and slips out like water. We’ve been staring at each other for months now, and while we haven’t spoken to each other, I’ve begun to call it Fido after the stuffed dog Mom bought me, convincing me it was a real one who didn’t need to eat or poop. The dog had been a faithful companion, receptive to my wandering conversations about where we went when we died, why UGGs cost so much money, where trash goes when it disappears from garbage cans. It took three months for me to suspect Mom’s words.

From behind the mirror, I watch Fido fill my shirt and pants with limbs resembling mine, although I swear they look fake, unable to hold up against gravity in the same way balsa wood snaps from an exhale. I wave. “Good luck,” I say, sitting down cross-legged on the cold concrete. If I focus on the dark stains on the walls and floors, the pipes winding around the ceiling, the tiny rectangular window too high for me to reach, this side of the mirror resembles an unfinished basement.

As I wait for Fido to return to switch places again with me (which I’m certain will happen once Fido realizes the real world isn’t all that), I look for an escape. Maybe Dad ended up spirited away into a mirror because he was always staring at his reflection. He was the type of person who smiled at cameras and made any angle flatter his profile even if no one was looking. Even when he let me sit on his shoulders, he’d tell me to avoid looping my arms around his neck otherwise I might cover his cheekbones from public view. Dad disappeared off the face of the planet. “That’s what happens to flaky men like him,” Aunt says because Mom can never admit it. “You’ve got to choose someone who’ll stick or fly solo.” I think of fried turnip cakes when Aunt tells me about sticky people—how they’d be stickier if you used less turnip, more rice flour, but then they’d also be denser yet less sink-in-your-stomach heavy without the water diluting the batter. I think I prefer them less sticky, more flavorful, even if I wind up more empty at the end. I wonder if Fido will get my preferences right—that I leave my shoes next to the slippers rather than by the rack, or that I use both a plate and a bowl because I can’t stand watching sauces mix with my rice. Not that, I suppose, Mom will notice. These days, she cares about a strict set of things outside of which gets flushed from her brain like a wimpy cache. This includes how often I stare in front of the mirror. I imagine her realizing I’ve been replaced. It might shock her into finally looking at me.

There’s not much beyond the long, rectangular mirror peering into the real world, but I’d rather not think of myself in prison because I chose to be here, and Fido chose to leave, and we’re all abiding by our freedom to head wherever opportunities open. I walk toward a wall and press my hand on the concrete, damp and cool to touch. The water must be coming from somewhere, trickling through pipes and seeking the ocean no matter how many man-made structures block its way. Things always find their way home, Mom likes to say when we get lost on the road because she keeps missing highway exits and we end up hours from home, finally returning once the traffic dies and she can switch lanes without panicking about cars behind her. Dad was the one who drove for any trip further than the grocery store, and even though he’d break the car like he’d been electrocuted, he was decisive, a dealbreaker for who was more likely to drive us to our deaths.

I walk along the wall, and the further I get from the mirror, the less I can see light reflecting where I came from. I peer upward, discovering a second window I hadn’t noticed before. It looks like it has been carved through the pavement, a hole patched with glass. I squint at the light coming in and reach for the bottom ledge of the window with my hands, the pads of my fingers scraping against the craggily concrete, and pull myself up, heaving my elbows and chest onto the ledge so my hands can rest. The glass clacks against the wall as I lean against it. I push the window open and crawl through.

This is what Mom calls running away. She’s a proponent of 吃苦, eating bitterness like it’s peanut butter from a jar or marshmallows plucked from cereal boxes or shumai. She encourages me to be patient and work harder when things don’t go my way, like when He Lao Shi had me stand in front of the classroom and recite the answers to every problem I got wrong because I’d scored the worst of everyone, exacerbated because I was a crybaby, tearing up when she criticized my handwriting for being too small and my pencil grip for being inefficient. I wanted to switch teachers but Mom said the other classes were full. Mom still took me out for ice cream afterward, because she knew cold treats quickly erased any seeds of grudges.

By some technicality, I guess I am running away like Dad did. Dad, who vanished according to Mom even though Aunt and I know he finally blew a fuse under her nagging—I shouldn’t call it blowing a fuse; Dad’s temper was near nonexistent. When he couldn’t handle something, he’d let it simmer, take a long walk along the road to the bridge crossing over the highway before coming home, lips dry and nose pink, ready for dinner. Rather Dad, who earned twice Mom’s salary as a pharmaceutical research scientist in diabetes in a country where people keep shoveling down sugar, must’ve decided he was wasting his life away and decided to build himself a new life without us, even though he promised he’d send me emails and texts. Mom had parental control programs installed on my phone so I told Dad not to risk it and he didn’t argue. I wish he did.

I consider it exploring rather than running away. After I pull my body through the window, I stand and rub my eyes, pupils adjusting to the light. I wonder if this is where Fido came from: this house, this room, this cheap circular kitchen table and marble countertops, these elastic yoga bands scattered on the hardwood like worms. It’s my house but brighter, like someone had gone through every room and sprayed a near-translucent layer of white paint over everything, poked holes in drywall to maximize sunlight. I rub my fingers on the wall, expecting white dust to flake off. I like the idea of taking bits of Fido’s world with me, smeared on my fingertips.

Mom, or someone who looks like Mom, stands in the kitchen, an apron patterned with azaleas and lanterns tied around her waist, kneading dough on the counter to make baozi, something only Dad used to make because Mom hated getting her hands sticky and refused to buy a bread maker capable of kneading. This version of Mom stands upright, fiercely pulling and stretching flour, her arm muscles tensing and relaxing as the weight of her body shifts back and forth. Her hair falls below her shoulders. The Mom I know has thin hair barely down to her ears, still growing back after chemotherapy. That’s why she eats so much tofu in sesame oil: sesame is good for your hair just as pork trotters are good for your skin, everyone knows that, she explained to me when dinner was pork trotter soup for the third day in a row. “How do I know I have good skin if I can’t look in the mirror?” I had asked one of those nights, poking the bone marrow out with a chopstick. “It’s all about the insides, if the insides are happy and healthy, the outside will be too,” she’d said. Then what’s the point of dermatologists, I refrained from asking. Mom had enough to worry about and I was happy she’d made it out of the study room for dinner. I think she suspected I might vanish like Dad did if she didn’t show her face more often. Fido must be in shock meeting Mom, prepared to run back to the mirror and demand I return to my rightful place. Fido didn’t seem like someone who could eat much bitterness, not based on all of our staring sessions—me observing Fido without blinking, Fido averting my gaze, looking towards something in the background. The wall. The window.

I slip back through the window before this mom can see me, nicking my cheek on the window ledge. My feet hit the concrete and I wince from the shock reverberating up my femur and spine. I’ll wait another hour and if Fido doesn’t return, I’ll need to find another way back. Fido doesn’t know Mom prefers barley tea over green tea but drinks green tea in the morning for the caffeine. Fido doesn’t know Mom forgets to turn on the light when it gets dark, and the glow of her monitor paints her face like a ghost. Only I know where the portable lamp is: suffocating in the closet, beneath a plastic bag stuffed with down covers, waiting for winter.

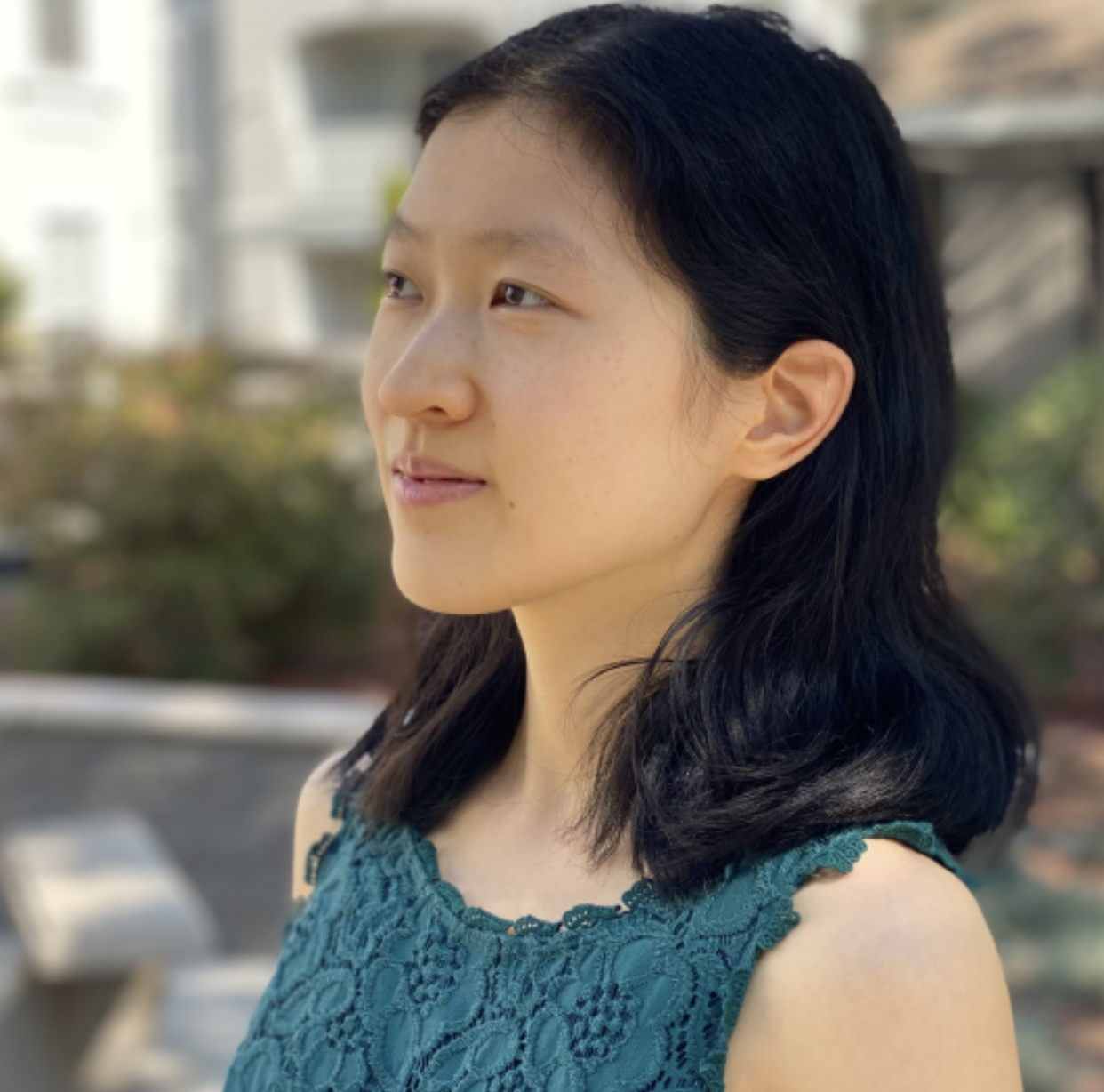

Lucy Zhang's chapbook HOLLOWED is forthcoming from Thirty West Publishing in 2022. Her work has appeared in Black Warrior Review, Contrary, DIAGRAM, New Orleans Review, Passages North, The Rumpus, West Branch & elsewhere, & has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, Best of the Net, & Best American Short Stories. Her work is anthologized in Best Microfiction 2021 & Best Small Fictions 2021, was a finalist in Best of the Net 2020 & was long listed in the Wigleaf Top 50. She is a fiction editor for Heavy Feather Review, assistant fiction editor for Pithead Chapel, & Flash Fiction Contributing Editor for Barren Magazine. Lucy lives in California.